Within financial planning, tax planning is traditionally viewed in the context of how a financial plan should be implemented. But tax planning can also be a starting point to determine what financial planning techniques may be appropriate for an investor’s portfolio. By understanding the mechanics of an investor’s Form 1040, it may be possible to reduce taxable income using standard financial planning techniques. The money saved in taxes is tangible and can be a significant aspect of the value of your financial planner.

There are four key areas to focus on:

1. Threshold Planning

The first key area of focus in tax planning is threshold planning. In a progressive tax system such as we have at the Federal level, tax rates increase as income rises. Therefore, managing income to keep the investor within a targeted tax bracket is essential to avoid overpaying taxes. Depending on an individual’s circumstances, they may be able to decrease, defer, or accelerate their income to optimize their tax liability.

Take the example of Janet. She is filing single and has an adjusted annual gross income of $155,000. She expects her income to increase substantially over the next few years. She wants to do some Roth conversions while still in a lower bracket. Hence, Janet can convert up to about $36,950 from her traditional IRA to a Roth this year while remaining in the 24% marginal tax bracket.

Kevin and Mary file jointly. They have a current taxable income of $388,000. That places them in the 32% tax bracket for the current tax year, but only barely. $4,100 of their income is taxed at 32%, while the other $83,900 is taxed at a top rate of 24%. With that insight, Kevin and Mary can reduce their income for the next tax year to keep their taxable amount under the 24% threshold, resulting in a tax savings of $1,312.

Nancy and Tom are also married filing jointly. They have combined annual salaries of $184,000, placing them in the 22% marginal tax bracket. They want to prepare for retirement by converting some of their Traditional Individual Retirement Account (IRA) into a Roth account. However, a one-time work bonus of $20,000 will push Nancy and Tom to the top of their current marginal tax bracket. A Roth conversion would be done at the 24% tax rate instead of 22%. Because they don’t expect more bonuses after this year, it may make sense to delay their Roth conversions to a future year when they will be taxed at the marginal rate of 22% instead of 24%.

The key takeaway is that understanding an investor’s current income compared to their future expectations informs the degree and magnitude of income adjustments required to optimize their tax situation.

2. Capital Gains Management

Capital gains are a critical component of gross income. They are generated by standard transactions such as rebalancing, a change in asset allocation, or gifting. They can also be generated within a mutual fund.

Mutual fund-level distributions

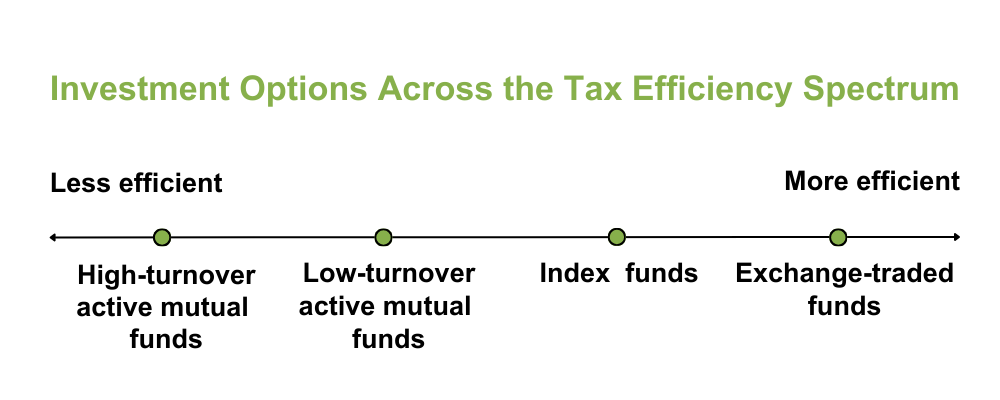

When a mutual fund makes a trade that results in a capital gain, the investor may become liable for a capital gains tax. The gains are difficult to plan for, and mutual fund companies typically shift them to investors at the end of the tax year. Investors can avoid mutual fund-generated taxes by shifting their portfolio into more tax-efficient investments. In particular, Exchange Traded Funds (ETFs) are generally more tax-efficient than mutual funds.

At the individual level, investors’ trade can also result in capital gains and, therefore, capital gains taxes. Typical trades can include rebalancing or repositioning an asset allocation.

Tax efficiency can be improved by redirecting these standard transactions. For example, fund distributions and proceeds from rebalancing or repositioning can be used as income instead of being automatically reinvested. This minimizes the need for additional transactions to generate cash. This approach can reduce the frequency of required rebalances by directing fund distributions into underweight positions.

Consider the example of Leslie and Jack, a retired couple that files jointly.

Leslie and Jack take periodic distributions from their taxable retirement account to help fund their spending needs.

Last year, they had ordinary income of $140,000 and capital gains of $22,000. On top of that, Leslie and Jack decided to take a cruise and needed to take $7,000 from their taxable accounts to fund it. Their portfolio is set up to reinvest dividends automatically and annual fund distributions. Qualified dividends and fund distributions accounted for $9,000 of those capital gains. Because the $9,000 was automatically reinvested, it was not received by or available as liquid to the couple.

After evaluating the couple’s annual spending needs, their financial planner adjusted their taxable accounts to have all proceeds from necessary transactions fund a cash account rather than be reinvested. The advisor also evaluated their account’s default cost basis method and adjusted it to avoid selling short-term holdings. Through these adjustments, the advisor was able to save the couple almost $1,200 in annual taxes.

Tax loss harvesting is the process of making lemonade out of a losing investment. As we all deplore, there will be investments that will lose money even in a good year and a well-diversified portfolio. The investor will book a capital gain loss by selling the losing investment.

While tax loss harvesting is akin to making lemonade, tax gain harvesting is more like making key lime pie. The investor can offset the capital gain against the capital losses by selling profitable investments. That will result in a tax-free gain. Then, the funds have to be reinvested for the cycle to start again.

Strategic harvesting can result in a portfolio in a taxable account that will incur fewer taxes and grow faster than accounts that are not strategically managed.

3. Income Exclusions

According to the Tax Code, Gross Income includes “all income, from any source … unless excluded elsewhere.” Income “excluded elsewhere” offers the best possibility for tax planning. However, few options are available, including municipal bond income and qualified distributions from Roth IRAs.

Municipal bond income is one such exclusion. Investors can lower their tax liability by switching from taxable bonds to tax-free municipal bonds. However, it’s important to compare the after-tax returns of municipal bonds with equivalent corporate bonds, as munis usually pay lower interest rates.

Depending on your tax bracket, you may be better off buying municipal bonds in a high tax bracket or taxable bonds in a comparatively low tax bracket.

Look at the example of Abby, who holds a taxable corporate bond that pays 5.15%. She wants to know what rate a muni bond would need to pay to yield an equivalent after-tax rate. For an investor in the 22% tax bracket, the muni bond must pay 4.017% to match the corporate bond’s yield.

Qualified distributions from Roth IRAs, Roth 401(k), and other Roth plans are also excluded from taxable income.

Roth contributions will not lower taxable income in the year of contribution. However, they can provide additional flexibility for threshold planning in the long term.

Making Roth contributions early in one’s career provides a few advantages. First, because the investor’s income is generally at its lowest early in a career, the tax on their Roth contribution is paid at their lowest tax rate. For example, an investor in a first job after college may work for just half the year following graduation. That investor might be in the 12% tax bracket for a large starting salary range.

Second, starting to contribute early allows more time for the Roth assets to grow in value, increasing the investor’s base of tax-free assets. Having a variety of account types helps with managing tax thresholds in retirement. Optimizing income distribution can be a complex process that balances withdrawals from taxable, tax-deferred, and Roth accounts to achieve the most tax-efficient combination. Understanding the investor’s anticipated income and cash flow can help identify the best approach. For example, investors with fairly consistent income may benefit from a balanced approach to distributing taxable and tax-free income. Investors with significant fluctuations in income may benefit from a more tactical approach.

4. Deductions

Maximizing deductions is another essential aspect of tax planning. Here are some deduction-related strategies:

Tax-Deferred Retirement Accounts

While Roth accounts provide benefits at the time of distribution, traditional tax-deferred accounts offer immediate tax relief. There are also several options, including 403(b) and 457 plans, but the most common alternatives are 401(k) plans and IRAs.

Although both 401(k)s and IRAs allow a dollar-for-dollar reduction in taxable income, they have different constraints. 401(k) contributions are reported as a separate non-taxable income. In contrast, IRA contributions are accounted for as a separate line item on the 1040 tax return.

Consider the example of Debbie, a single taxpayer. Debbie contributes to his 401(k) but not at the maximum rate. Debbie also contributes to her IRA. However, her income exceeds the income limit for deductible IRA contributions this year. She can maximize her tax deduction by contributing to her 401(k) instead.

Standard and Itemized Deductions

Thinking about deductions in a broader sense. When you file your taxes, you can choose between taking specific itemized deductions or a standard deduction available to all taxpayers. Itemized deductions include mortgage interest, state and local taxes, and charitable contributions. On the other hand, the standard deduction is a fixed amount you can choose to claim instead of itemizing.

To maximize your deductions, you’ll want to compare the total of your itemized deductions for the year with the standard deduction and select the higher of the two. But here’s where long-term planning can come into play. By thinking ahead over several years, you can strategically time when you itemize your deductions to get the most significant benefit.

Maximizing Charitable Deductions

Charitable contributions can be a great way to support causes you care about while lowering your taxable income. Note that, typically, you can only claim a charitable donation deduction if your total itemized deductions exceed the standard deduction. This means that people who make smaller, periodic charitable gifts will likely miss the tax benefits.

To maximize the deductibility of charitable donations, taxpayers can bundle multiple years’ contributions into a single year. You can achieve this by using a donor-advised fund (DAF). A DAF acts like a holding account for your charitable contributions, allowing you to make periodic donations. In the years when you make these bundled charitable gifts, you may surpass the standard deduction and enjoy the tax benefits. In the years when you don’t contribute, you can take the standard deduction without losing any benefits. This strategic approach can boost your overall tax situation.

For example, let’s meet Joyce and Hank, who file their taxes jointly. Joyce and Hank have various itemized deductions, including mortgage interest, state and local taxes, and charitable gifts, totaling $26,000 annually. This amount is slightly below their standard annual deduction of $29,200. Since they could claim the standard deduction regardless of their charitable contributions, they would only benefit from itemizing their deductions if they plan to give more than $3,200).

However, by adopting a new charitable gifting strategy and contributing two years’ worth of donations every other year using a Donor Advised Fund, Joyce and Hank can secure an additional deduction of $4,300 in year one and $3,700 in year three. During the years when they don’t contribute, they can still use the standard deduction.

Health Care Expenses

Medical expenses can be significant, and you may be able to deduct them if they exceed a certain threshold. To qualify for a deduction, your out-of-pocket medical expenses must exceed 7.5% of your adjusted gross income (AGI). This calculation takes into account various income exclusions and above-the-line deductions.

One strategy to maximize your medical expense deduction is to use a bunching strategy. This involves shifting the payment of multiple years’ worth of medical expenses into a single year when they exceed the 7.5% threshold.

Another approach is to utilize a Health Savings Account (HSA) with a High Deductible Health Plan (HDHP). An HSA allows you to set aside money for future medical expenses. Your contributions to an HSA offer a triple tax advantage: they’re fully deductible, they can be invested and grow tax-deferred, and withdrawals are tax-free when used for qualified medical expenses.

Take Jenni and Mark, for example. They have two children on their health plan and are evaluating their insurance options. They have considerable assets and are in good health, which makes it unlikely that they’ll meet the threshold for itemizing medical expenses. Comparing their HDHP option with a non-HDHP option, they see clear benefits to the HDHP. It enables them to contribute $8,300 to a tax-deferred account and provides additional tax deductions for the year.

When you’ve determined that an HDHP/HSA combination is the right choice, you must decide whether to pay for medical expenses out of pocket or use the HSA. One significant advantage of an HSA is that there are no annual distribution requirements or time limits on use. This means the HSA can continue to grow, providing a valuable source of triple-tax-free income during your retirement years.

These strategies, such as optimizing deductions and using tax-advantaged accounts, can help you reduce your taxable income and save more of your hard-earned money. They’re not just for tax experts; with some planning and knowledge, anyone can employ them to their financial advantage.

Conclusion

There are several strategies that taxpayers like you can integrate into your financial planning. Effective tax planning can lead to substantial savings and improved investor financial outcomes. Understanding the various strategies available allows you to optimize your tax efficiency, reduce your tax liability, and make informed decisions about your financial future.

Note: This article is based on the 2024 tax code. All references to tax in this article are specific to federal income tax unless otherwise noted. This article highlights common tax-saving opportunities.