[thrive_headline_focus title=”Investment risk is an inevitable part of capital markets.” orientation=”left”]

Markets do not just go up as much as we wish for that to be always the case.

Markets do not just go up as much as we wish for that to be always the case.

Sometimes capital markets experience stress and the draw-downs can be extremely uncomfortable to investors.

How investors react to periods of capital market stress is incredibly important.

Become too aggressive and you could end up with major short-term losses and your financial survival may be at stake.

On the other hand, become too cautious and you may end up excluded from any future capital market appreciation.

So, if risk is inevitable, what can you do about it? Being either extremely aggressive or extremely risk-averse are probably the least desirable options especially if you wait to act until there is a market meltdown.

In the first case, you may not be able to stay invested as short-term losses cripple your psyche and your pocketbook. Even though you believe in your investments, your emotions will be tugging at you and second-guessing you. This is the curse of being too early.

In the case where people become too risk-averse, being too cautious prevents you from making up the losses experienced during periods of capital market stress by participating in the good times. Most likely you second guess yourself and by the time you take the plunge back in you have probably already missed out on some large gains. This is the curse of being too late.

Investing is not easy especially when things go against you in the short-term. It is best to understand what you are getting yourself in and have a plan for when things go awry. As Mike Tyson once said, “everybody has a plan until they get punched in the nose”.

Getting punched in the nose is not an uncommon experience for stock market investors. For bond market investors the experience is not as common but it still happens.

Understanding that investing can at times be brutally taxing on your pocketbook and psyche is an essential element of reaping the benefits of any investment plan. A great game plan is useless unless you have the ability to withstand the dark periods.

Investors are frequently confused by capital market behavior. Over the short-term asset classes can go almost anywhere as investment sentiment is usually a strong driver of returns. Market pundits attempt to provide some rationale for why things are moving in a certain direction, but in reality, most of what goes on from day to day in capital markets is usually nothing more than noise.

Markets are prone to bouts of over-confidence where all the bad news gets ignored and investors appear overly upbeat. Other times, markets will be laser-focused on negative short-term events of little economic significance and investors will become overly pessimistic. Even seasoned investment professionals feel sometimes that there is no rhyme or reason for what is happening to financial asset prices.

Over longer-term horizons, asset class fundamentals start being reflected in prices as investment sentiment becomes secondary. Profits, valuations, profitability, growth potential become the drivers of prices. Periods of stress are frequently forgotten and appear as mere blips on historical price charts.

One of the key tenets of long-term investing is that risk and return are inextricably tied together. Without any risk, you should not expect any incremental returns. Investing is inherently risky as outcomes – short or long-term – cannot be predicted with total certainty.

Most investors understand that, on average, stocks do better than bonds but that the price of these higher returns is a lot more risk. Investors also understand that longer-maturity bonds will do better most of the time than simply purchasing a CD at the local bank or investing in a money market mutual fund.

But beyond this high-level understanding of capital market behavior, there is lots of confusion. Gaining a better understanding of key asset class risk and return relationships will help you become a better-informed consumer of investment strategies.

Understanding what you are getting yourself in when evaluating different investment strategies could significantly alter your wealth profile for the better and allow you to take advantage of market panics rather than simply react to crowd psychology like most people.

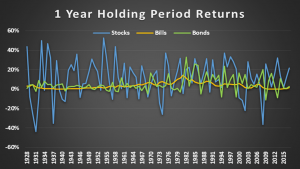

To become an informed consumer of investment strategies the first step is understanding key asset class risk and return tradeoffs. We use a dataset kindly provided online by Professor Aswath Damadoran at NYU to look at calendar year returns on US stock, bond and bill returns. Bond returns proxy for a 10-year constant maturity US Treasury Note and bills correspond to a 3 month US t-bill. US stocks are large capitalization stocks equivalent to the S&P 500. Figure 1 depicts the annual asset class returns since 1937.

The first thing that jumps out from the chart is the much higher level of return variability of stocks.

The second thing that jumps out is the incredible year over year smoothness of T-bill returns. Bonds are clearly somewhere in between with volatility characteristics much more similar to bills.

The third thing that jumps out are the rare but eye-popping large equity market meltdowns such as during 1937, 1974, 2002 and 2008. Lastly, of notice are the very large positive spikes in equity returns during years such as 1954, 1958, 1975, 1995 and 2013.

Figure 1

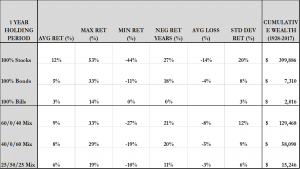

What is not entirely clear from looking at the yearly return chart is the huge cumulative out-performance of stocks relative to both bonds and bills. Table 1 provides summary statistics on calendar year returns for each asset class.

What is not entirely clear from looking at the yearly return chart is the huge cumulative out-performance of stocks relative to both bonds and bills. Table 1 provides summary statistics on calendar year returns for each asset class.

Table 1

Key highlights:

- Over the 1928-2017 period, stocks have returned on average 12% per year with an annual standard deviation of 20% year. Bonds are next in line with an average return of 5% and a volatility of 8%. Bills have had the lowest rate of return at 3% with a volatility of 3%. These numbers correspond to the usual risk/reward relationships that investors know all about.

- In 27% of the years between 1928 and 2017, stocks have had a negative return. The average return when the market has gone down is -14%. Nobody likes losses but even bond investors saw negative returns in 18% of the years and when they happened the average loss was -4%. The only way never to lose money in any given year is to invest in bills.

- If one had invested $100 in December 1927 and held that investment the ending portfolio value would be $399,886 – a huge rate of growth despite the infrequent yet terrifying equity market meltdowns. Bonds don’t come even close with an ending portfolio balance of $7,310. Playing it safe with bills would have yielded a portfolio value of $2,016.

- From a cumulative wealth perspective, stocks are clearly the superior asset class but only if the investor is able to stomach the rare but large equity drawdowns and seeing losses in over a quarter of the years.

- If the investor is seeking stability with no chance of principal loss, T-bills are the preferred asset class. The rewards compared to stocks will be meager, but the ride will be smooth and predictable.

What happens when you extend the holding period out to, say 10 years? Does the spikiness of stock market returns disappear? What about the frequency of down years?

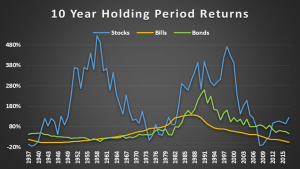

Using the same data set as before and forming rolling 10-year holding returns starting in 1927 we observe in Figure 2 that some of the volatility of stocks and bonds has dissipated. Instead of spikes we now have mountains and slopes.

Figure 2

The chart on rolling 10-year returns exposes the massive cumulative out-performance of stocks during most ten-year holding periods. There are instances of negative 10-year stock returns (6% as shown in Table 2) but they are swamped by the mountain of positive returns especially when viewed in relation to bond and bill returns.

We see only three periods when equity investors would have loved to play it safe and be either in bonds or bills – the early years post the Great Depression (1937-39), the Financial Crisis (2008-9), and economic stagnation and inflationary years starting in the mid-70s through the beginning of the equity bull market of 1982. In the first two instances, equity holders lost money. In the latter instance, equity investors enjoyed positive returns but below those of either bonds or bills.

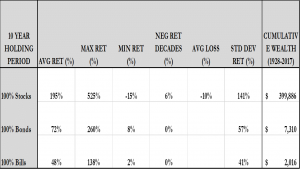

Table 2

Some observations are in order:

- As one extends the holding period from 1 to 10 years some of the spikiness of one-year returns is smoothed out – not every year is fantastic and not every year is terrible, periods of stress are usually followed by periods of recovery and so on

- Over a ten year holding period stocks do not look as scary – only in 6% of our observations do we see a negative return. When those losses occur the average loss is 10% on a cumulative basis.

- Rolling 10-year maturity bonds every year over a decade yields no periods in our sample where the strategy exhibits a loss. The same holds true for bills.

- Investors able to extend holding periods from short to longer maturities such as ten years significantly lower their odds of seeing negative returns as confirmed in the empirical data

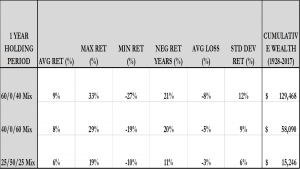

What happens when we mix and match asset classes? Does that help lower our probability of loss? We look at some typical multi-asset class mixes over one-year holding periods:

- The 60/0/40 portfolio composed of 60% stocks and 40% bonds – a traditional industry benchmark

- The 40/0/60 portfolio composed of 40% stocks and 60% bonds – a moderately conservative mix

- The 25/50/25 portfolio composed of 25% stocks, 50% bills and 25% bonds – a conservative mix for a very risk-averse investor

Mixing asset classes is usually referred to as multi-asset class investing. The premise for such an approach is based on the diversification benefits afforded by allocating in varying proportions to asset classes with their own unique risk and return characteristics.

It turns out that over the 1928-2017 period stocks were essentially uncorrelated to both bonds and bills. The correlation between bonds and bills was 0.3. Building portfolios with lowly correlated asset classes is hugely beneficial in terms of lowering the volatility of the multi-asset class mix.

Table 3

What are the main conclusions that we can reach when mixing asset classes with widely different risk and return characteristics?

- When combining stocks, bonds, and bills in varying proportions we arrive at portfolio results that fall between those of equities and bonds

- The traditional 60/0/40 portfolio had a lower frequency of negative returns compared to an all-equity portfolio, significantly lower volatility and a cumulative ending portfolio value only about a 1/3 as large. What you gain in terms of lower risk, you lose in terms of compound returns.

- The 40/0/60 portfolio which represents a lower risk alternative to the investor lowers volatility (to 9%) but at the expense of also lowering average returns (to 8%) and especially cumulative wealth (ending value of $58,090)

- The lowest risk multi-asset class strategy that we looked at – the 25/50/25 portfolio – had the lowest average returns (6%), lowest volatility (6%) and lowest long-term growth.

- A key implication of multi-asset investing is by combining asset classes with disparate risk and return characteristics you can build more attractive portfolios compared to single asset class portfolios

- Comparing two traditionally low-risk portfolios – 100% bonds and the 25/50/25 portfolio – demonstrates the benefits of multi-asset class investing. The multi-asset class portfolio not only has higher average returns but lower risk. The frequency of calendar year loss is smaller (11% compared to 18%) and the long-term portfolio growth is over 2X that of the all-bond portfolio.

Three very significant lessons emerge from our study of asset class behavior that can vastly improve your financial health. The first relates to the holding period. Specifically, by having a longer holding period many of the daily and weekly blips that so scare equity investors tend to wash away.

Equity investments do not look as volatile or risky when judged over longer holding periods of say 10 years.

The second lesson relates to the power of compounding. Small differences in average returns can yield huge differences in long-term cumulative wealth. In terms of the multi-asset class portfolios – the 60/0/40 versus the 40/0/60 – yields only a 1% average return difference but a 2X difference over the 1928-2017 period.

Seemingly small differences in average calendar year returns can result in massive wealth differences over long holding periods.

The third lesson relates to diversification. By mixing together asset classes with varying risk and return characteristics we can significantly improve the overall attractiveness of a portfolio. Lower portfolio risk is achievable with proper diversification without a proportional sacrifice in terms of returns. Properly constructing multi-asset class portfolios can yield vastly superior outcomes for investors.

Every investor needs to come to terms with the risk to reward relationships of major asset classes such as stocks, bonds, and bills. Understanding the risk and return tradeoffs you are making is probably the most important investment decision affecting the long-term outcome of your portfolio.

Some investors can stomach the sometimes wild ride offered by stocks and choose to overwhelmingly use equity strategies in their portfolios. They don’t worry much about the daily vicissitudes of the stock market. They accept risk in return for higher expected returns.

Not everybody, however, can stomach the wild ride that sometimes comes from owning stocks despite understanding that over the long-term stocks tend to better than bonds and bills.

Some investors are willing to leave a bit of money (but not too much, please) on the table in return for a smoother ride. They may elect to hedge some of the risks. Or they may mix in varying proportions of risky and less risky asset classes and strategies.

Yet other investors are so petrified of losses and market volatility that they will forego any incremental return for the comfort and steadiness of a safe money market account. They choose to avoid risk at all costs.

Which is the better approach for you? Avoid all risks, save a lot and watch your investment account grow slowly but smoothly?

Or, take some risk, sweat like a nervous high schooler when capital markets go bust and grow your portfolio more rapidly but with some hiccups?

The answer depends on you – your needs, goals and especially your attitude toward risk and your capacity to absorb losses to your wealth. If you already have a financial plan in place great. If you need help getting started or refining your plan, the team at Insight Financial is ready to share our expertise and bring peace of mind to your financial life. Book an appointment here.

Understanding that investing can at times be brutally taxing on your pocketbook and psyche is an essential element of reaping the benefits of any investment plan. In subsequent articles, we will be exploring different ways of managing risk and structuring portfolios.